Age-related hearing loss has wider ramifications

The Impact of hearing loss on health Issues such as cognition and dementia should be recognized and managed

Hearing loss affects an estimated 5 percent of the world’s population, and will affect twice that number (900 million) in 30 years. The majority of these will be adults and especially the elderly because of the declining population (in the developed world) with increasing longevity.

Besides the obvious disability that hearing loss is associated with are other equally compelling health issues that are important to recognise, prevent or manage. Cognitive impairment, dementia, depression and social isolation are several of the conditions that are associated with hearing loss in the elderly.

The aim of this article is to explain the fundamentals of the ear, mechanisms of hearing and the causes of hearing loss in the elderly briefly. Thereafter, a discussion on the impact of hearing loss on cognition and dementia is provided with ways of delaying these conditions.

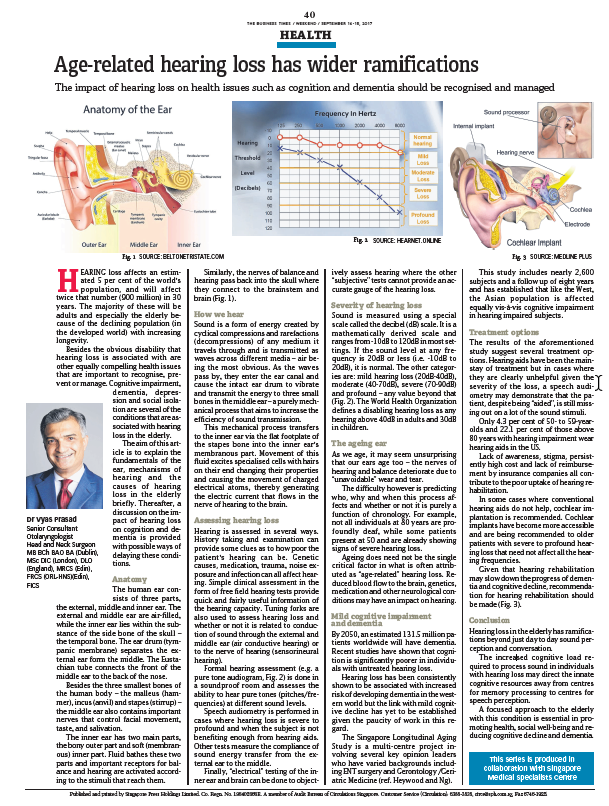

Anatomy

The human ear consists of three parts, the external, middle ear and inner ear. The external and middle ear are air-filled, while the inner ear lies within the substance of the side bone of the skull – the temporal bone. The ear drum (tympanic membrane) separates the external ear from the middle. The Eustachian tube connects the front of the middle ear to the back of the nose.

Besides the three smallest bones of the human body – the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil) and stapes (stirrup) – the middle ear also contains important nerves that control facial movement, taste and salivation.

The inner ear has two main parts, the bony outer part and soft (membranous) inner part. Fluid bathes these two parts and important receptors for balance and hearing are activated according to the stimuli that reach them. Similarly, the nerves of balance and hearing pass back into the skull where they connect to the brainstem and brain.

How we hear

Sound is a form of energy created by cyclical compression and rarefactions (decompression) of any medium it travels through and is transmitted as waves across different media – air being the most obvious. As the waves pass by, they enter the ear canal cause the intact ear drum to vibrate and transmit the energy to three small bones in the middle ear – a purely mechanical process that aims to increase the efficiency of sound transmission.

This mechanical process transfers to the inner ear via the flat footplate of the stapes bone into the inner ear’s membranous part. Movement of this fluid excites specialized cells with hairs on their end changing their properties and causing the movement of charged electrical atoms, thereby generating electric current that flows in the nerve of hearing to the brain.

Assessing hearing loss

Hearing is assessed in several ways. History taking and examination can provide some clues as to how poor the patient’s hearing can be. Genetic causes, medication, trauma, noise exposure and infection can all affect hearing. Simple clinical assessment in the form of free field hearing tests provide quick and fairly useful information of the hearing capacity. Tuning forks are also used to assess hearing loss and whether or not it is related to conduction of sound through the external and middle ear (air conductive hearing) or to the nerve of hearing (sensorineural hearing).

Formal hearing assessment (eg. a pure tone audiogram) is done in a soundproof room and assesses the ability to hear pure tones (pitches / frequencies) at different sound levels)

Speech audiometry is performed in cases where hearing loss is severe to profound and when the subject is not benefiting enough from hearing aids. Other tests measure the compliance of sound energy transfer from external ear to the middle.

Finally, “electrical” testing of the inner ear and brain can be done to objectively assess hearing where the other “subjective” tests cannot provide an accurate gauge of the hearing loss.

Severity of hearing loss

Sound is measured using a special scale called the decibel (dB) scale. It is a mathematically derived scale and ranges from -10dB to 120dB in most settings. If the sound level at any frequency is 20dB or less (i.e. -10dB to 20dB), it is normal. The other categories are: mild hearing loss (20dB – 40dB), moderate (40dB – 70dB), severe (70dB – 90dB) and profound – any value beyond that. The World Health Organization defines a disabling hearing loss as any hearing above 40dB in adults and 30dB in children.

The ageing ear

As we age, it may seem unsurprising that our ears age too – the nerves of hearing and balance deteriorate due to “unavoidable” wear and tear.

The difficulty however is predicting who, why and when this process affects and whether or not it is purely a function of chronology. For example, not all individuals at 80 years are profoundly deaf, while some patients present at 50 and are already showing signs of severe hearing loss.

Ageing does need not be the single critical factor in what is often attributed as “age-related” hearing loss. Reduced blood flow to the brain, genetics, medication and other neurological conditions may have an impact on hearing.

Mild cognitive impairment and dementia

By 2050, an estimated 131.5 million patients worldwide will have dementia. Recent studies have shown that cognition is significantly poorer in individuals with untreated hearing loss.

Hearing loss has been consistently shown to be associated with increased risk of developing dementia in the western world but the link with mild cognitive decline has yet to be established given the paucity of work in this regard.

The Singapore Longitudinal Aging Study is a multi-centre project involving several key opinion leaders who have varied backgrounds including ENT surgery and Gerontology / Geriatric Medicine (ref. Heywood and Ng). This study includes nearly 2,600 subjects and a follow up of eight years and has established that like the West, the Asian population is affected equally vis-a-vis cognitive impairment in hearing impaired subjects.

Treatment options

The results of the aforementioned study suggest several treatment options. Hearing aids have been the mainstay of treatment but in cases where they are clearly unhelpful given the severity of the loss, a speech audiometry may demonstrate that the patient, despite being “aided”, is still missing out on a lot of the sound stimuli.

Only 4.3 percent of 50- to 59-year-old and 22.1 percent of those above 80 years with hearing impairment wear hearing aids in the US.

Lack of awareness, stigma, persistently high cost and lack of reimbursement by insurance companies all contribute to the poor uptake of hearing rehabilitation.

In some cases where conventional hearing aids do not help, cochlear implantation is recommended. Cochlear implants have become more accessible and are being recommended to older patients with severe to profound hearing loss that need not affect all the hearing frequencies.

Given that hearing rehabilitation may slow down the progress of dementia and cognitive decline, recommendation for hearing rehabilitation should be made.

Conclusion

Hearing loss in the elderly has ramifications beyond just day to day sound perception and conversation. The increased cognitive load required to process sound in individuals with hearing loss may direct the innate cognitive resources away from centres for memory processing to centres for speech perception.

A focused approach to the elderly with this condition is essential in promoting health, social well-being and reducing cognitive decline and dementia.

Business Times

14-15 September 2019