Throat cancer refers primarily to malignant tumours of the voice box and the lining of the muscular tube that lies behind it. The main risk factors are smoking and alcohol and these are synergistic when both factors are present. Throat cancer usually affects older males but it can also affect younger patients of any gender who are non-smokers and non-drinkers too. This article aims to inform the reader of the structure, disease process and management of this type of cancer and what to watch out for to avoid unnecessary delay in treatment.

Anatomy and physiology

The throat is a complex structure consisting of the muscular tube (pharynx) that connects the back of the nose and throat to the gullet (oesophagus) and voice box (larynx). It allows for the safe flow of food and fluids to the gullet and of air through the larynx into the lungs. The larynx consists of muscles, cartilage and nerves which are designed to safeguard the airway, protecting it from potential entry of food and drinks by “closing” itself off. This reflex is paramount in survival and is what allows us to thereafter generate immense force from our lungs to produce a cough to clear the airway. Failure to do so can result in choking and lead to chest infections such as pneumonia.

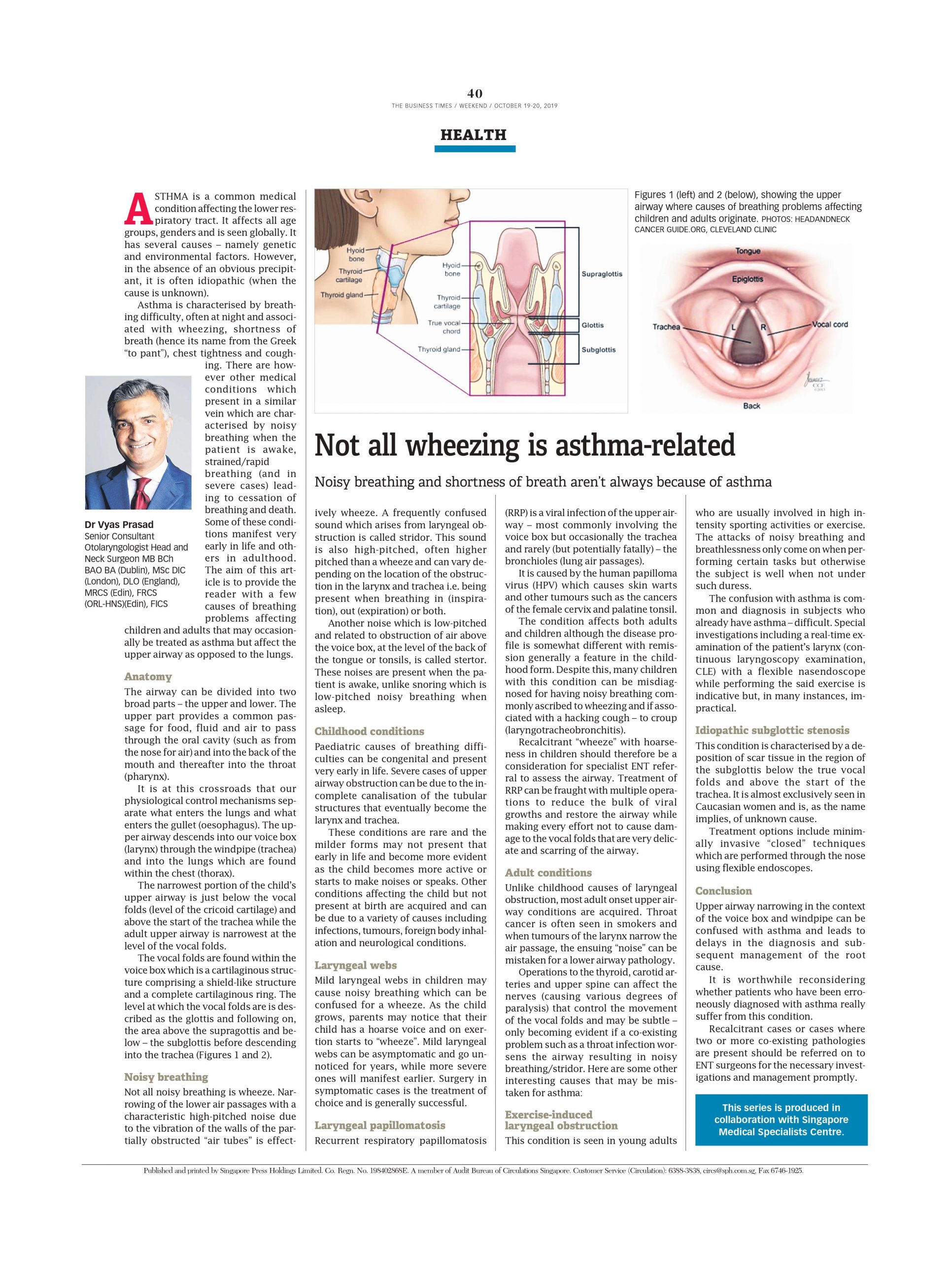

Other functions of the larynx include voicing and the capacity to strain and raise the abdominal pressure. There are three main parts of the larynx (Fig 1): the upper part is the supraglottis; the middle, the glottis – where the vocal folds/cords are located; and the lower part is the subglottis, where the voice box joins the windpipe (trachea). The lining of the throat is known as its mucosa. It is the toxic irritation of cigarettes and alcohol with their chemical compounds that alter the cells of the mucosa causing them to change their appearance and behaviour leading to an irreversible genetic alteration and to cancer. Genetic factors, exposure to certain chemicals and chronic exposure to acid, viral infections and other irritants have been postulated as causes in other patients.

Symptoms and signs

Patients with throat cancer present in several ways. Hoarseness in patients with no obvious precipitating cause exceeding a fortnight should be referred on for specialist investigation. Lesions on the true vocal folds affect their vibratory capacity and result in an abnormal rough voice. If the mass of the tumour or its extension reduce the mobility of either or both cords, the voice can sound breathy too. Swallowing difficulties and choking are also symptoms that can be present as signs of possible throat cancer.

Throat or ear pain on swallowing are also important complaints that warrant investigation. Blood in the saliva and increasing noise while breathing and shortness of breath can be later features of throat cancer and warrant rapid referral to an ENT surgeon. Patients with extension of their cancers may, rarely, present with disease that has spread to the lymph nodes in their neck which are often painless and hence should be seen urgently for further assessment.

History and examination

A full history is sought and risk factors ascertained. The state of the patient is appraised to assess the severity of the disease, especially in cases where the airway is either compromised physically, potentially leading to asphyxia, or in its inability to protect the lungs from aspiration of ingested solids and liquids. Thereafter, patients are examined with particular attention paid to their larynx, back of the tongue and side of their throats. This is achieved using a flexible fiberoptic endoscope known as a nasendoscope which is passed via the nostril, through the nose and above the voice box. Other methods of examining the larynx include using a laryngeal mirror and rigid endoscopes that are angled so they can visualise the throat through the mouth.

Investigations

Imaging of the neck and throat are achieved using sophisticated cross-sectional imaging modalities such as an MRI or CT scan. Further investigation includes examining the patient’s upper aerodigestive tract under a general anaesthetic with concomitant biopsies of the lesion/s in question with analysis by the pathologist. Thereafter, the confirmed cancer is staged and treatment recommended after discussion in a multi-disciplinary tumour board made up of specialist oncologists in surgery, radio and chemotherapy, pathology, radiology and specialist nurses, speech therapists and dietitians.

Treatment

Throat cancer may present at various stages, often divided into early or late. There are also pre-cancerous stages that if untreated may develop into cancer. Hence, treatment is tailored to the disease and patient along with risk factors such as persistent smoking, drinking etc. Early cancers can be treated with a single modality of treatment – that is, either by surgery alone or radiotherapy.

The decision to use a particular modality is made based on the site and accessibility of the tumour, the ensuing risks to the voice and swallow and cost. Minimally invasive surgery utilising lasers (Figure 2A and 2B) has been well established as an effective method to treat laryngeal cancer. It is very accurate and can be repeated unlike radiotherapy that is often a one-off treatment and therefore rarely repeatable.

More advanced cancers require more aggressive treatment including the incorporation of chemotherapy where applicable to radiotherapy. Transoral robotic surgery has also been used to great success and in cases where patients may have already had radiotherapy and salvage surgery is advocated but carries higher risks of complications. Open surgery has become less common currently as “laryngeal preservation” is advocated to avoid what is generally a mutilating removal of the voice box with subsequent permanent changes to the patient. Total laryngectomy, however, in cases of advanced cancer is still a very oncologically sound and effective operation.

Voice rehabilitation

With the loss of the larynx comes the obvious loss of the capacity to speak. Along with this is the fact that the patient’s throat is no longer at the junction box between the airway (trachea) and food way (oesophagus). The patient therefore has a complete separation between the two tubes with the windpipe now attached to the skin of the neck below the removed voice box.

Various ways of voice rehabilitation have been developed including “oesophageal speech” where the patient swallows air and belches it out in a controlled manner causing vibration of the back of his tongue, mouth and lips while moving his tongue to speak. Other ways include the use of a speech valve – a purpose-built device that is inserted through the back wall of the windpipe into the oesophagus. This valve allows for the channelling of air from the lungs into the oesophagus and similarly out through the mouth causing vibrations that result in sound.

An electronic device that resembles a microphone known as an electrolarynx can be used and this transfers vibrations from the cheek to the device.

Finally, some patients rely on sign language and writing to communicate.

Conclusion

Laryngeal cancer is a cancer that can affect the young and old. It is seen in non-smokers and non-drinkers too. Symptoms that affect the voice box and throat that do not improve after a fortnight or so such as hoarseness, pain, swallowing problems, cough and shortness of breath should be referred on for specialist input quickly.