Glaucoma is a silent disease, and opportunistic screening and regular monitoring are recommended to detect it early

The recent haze ended as quickly as it began and the skies in Singapore are blue again. In medical parlance, such episodic problems are usually termed an “attack”, such as a heart attack, a gout attack or more relevant to my profession, a glaucoma attack. After each annual episode of “haze attack”, our region seems to bounce back, finger-pointing subsides and life returns to normalcy, until the attack repeats again the following year.

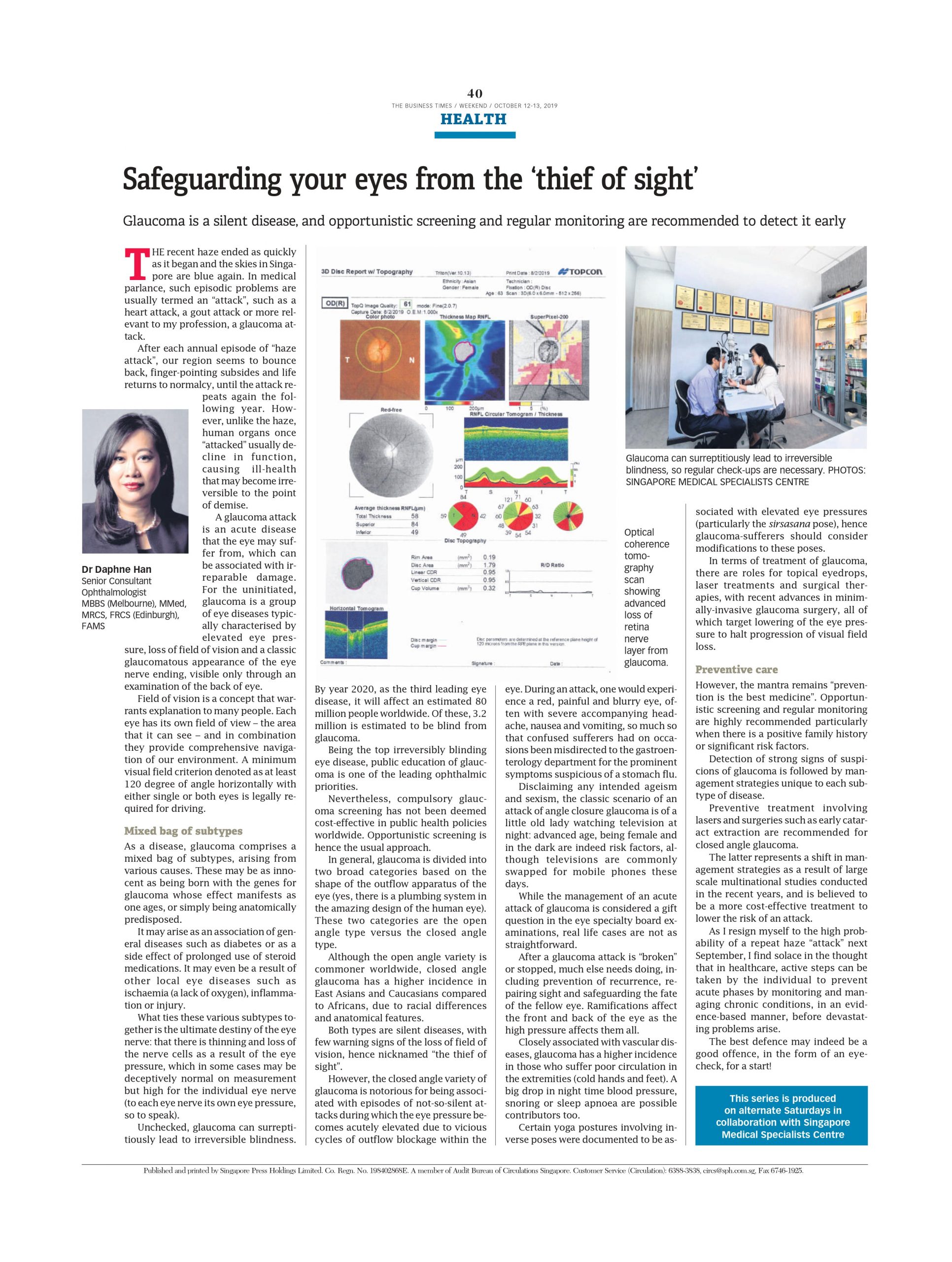

However, unlike the haze, human organs once “attacked” usually decline in function, causing ill-health that may become irreversible to the point of demise. A glaucoma attack is an acute disease that the eye may suffer from, which can be associated with irreparable damage. For the uninitiated, glaucoma is a group of eye diseases typically characterised by elevated eye pressure, loss of field of vision and a classic glaucomatous appearance of the eye nerve ending, visible only through an examination of the back of eye.

Field of vision is a concept that warrants explanation to many people. Each eye has its own field of view – the area that it can see – and in combination they provide comprehensive navigation of our environment. A minimum visual field criterion denoted as at least 120 degree of angle horizontally with either single or both eyes is legally required for driving.

Mixed bag of subtypes

As a disease, glaucoma comprises a mixed bag of subtypes, arising from various causes. These may be as innocent as being born with the genes for glaucoma whose effect manifests as one age, or simply being anatomically predisposed. It may arise as an association of general diseases such as diabetes or as a side effect of prolonged use of steroid medications. It may even be a result of other local eye diseases such as ischaemia (a lack of oxygen), inflammation or injury.

What ties these various subtypes together is the ultimate destiny of the eye nerve: that there is thinning and loss of the nerve cells as a result of the eye pressure, which in some cases may be deceptively normal on measurement but high for the individual eye nerve (to each eye nerve its own eye pressure, so to speak). Unchecked, glaucoma can surreptitiously lead to irreversible blindness.

By year 2020, as the third leading eye disease, it will affect an estimated 80 million people worldwide. Of these, 3.2 million is estimated to be blind from glaucoma. Being the top irreversibly blinding eye disease, public education of glaucoma is one of the leading ophthalmic priorities. Nevertheless, compulsory glaucoma screening has not been deemed cost-effective in public health policies worldwide. Opportunistic screening is hence the usual approach.

In general, glaucoma is divided into two broad categories based on the shape of the outflow apparatus of the eye (yes, there is a plumbing system in the amazing design of the human eye). These two categories are the open angle type versus the closed angle type. Although the open angle variety is commoner worldwide, closed angle glaucoma has a higher incidence in East Asians and Caucasians compared to Africans, due to racial differences and anatomical features.

Both types are silent diseases, with few warning signs of the loss of field of vision, hence nicknamed “the thief of sight”. However, the closed angle variety of glaucoma is notorious for being associated with episodes of not-so-silent attacks during which the eye pressure becomes acutely elevated due to vicious cycles of outflow blockage within the eye. During an attack, one would experience a red, painful and blurry eye, often with severe accompanying headache, nausea and vomiting, so much so that confused sufferers had on occasions been misdirected to the gastroenterology department for the prominent symptoms suspicious of a stomach flu.

Disclaiming any intended ageism and sexism, the classic scenario of an attack of angle closure glaucoma is of a little old lady watching television at night: advanced age, being female and in the dark are indeed risk factors, although televisions are commonly swapped for mobile phones these days. While the management of an acute attack of glaucoma is considered a gift question in the eye specialty board examinations, real life cases are not as straightforward.

After a glaucoma attack is “broken” or stopped, much else needs doing, including prevention of recurrence, repairing sight and safeguarding the fate of the fellow eye. Ramifications affect the front and back of the eye as the high pressure affects them all. Closely associated with vascular diseases, glaucoma has a higher incidence in those who suffer poor circulation in the extremities (cold hands and feet). A big drop in night-time blood pressure, snoring or sleep apnoea are possible contributors too.

Certain yoga postures involving inverse poses were documented to be associated with elevated eye pressures (particularly the sirsasana pose), hence glaucoma-sufferers should consider modifications to these poses. In terms of treatment of glaucoma, there are roles for topical eyedrops, laser treatments and surgical therapies, with recent advances in minimally-invasive glaucoma surgery, all of which target lowering of the eye pressure to halt progression of visual field loss.

Preventive care

However, the mantra remains “prevention is the best medicine”. Opportunistic screening and regular monitoring are highly recommended particularly when there is a positive family history or significant risk factors. Detection of strong signs of suspicions of glaucoma is followed by management strategies unique to each subtype of disease. Preventive treatment involving lasers and surgeries such as early cataract extraction is recommended for closed angle glaucoma.

The latter represents a shift in management strategies as a result of large-scale multinational studies conducted in the recent years, and is believed to be a more cost-effective treatment to lower the risk of an attack. As I resign myself to the high probability of a repeat haze “attack” next September, I find solace in the thought that in healthcare, active steps can be taken by the individual to prevent acute phases by monitoring and managing chronic conditions, in an evidence-based manner, before devastating problems arise.

The best defence may indeed be a good offence, in the form of an eyecheck, for a start!

Dr Daphne Han

Senior Consultant Ophthalmologist

MBBS (Melbourne), MMed, MRCS, FRCS (Edinburgh), FAMS

THE BUSINESS TIMES WEEKEND, OCTOBER 12-13, 2019